Report Campaign 2012

11st Season Report: January 9th – February19th

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The Supreme Council of Antiquities in Cairo has been extremely helpful in every way, and we are most grateful to the Minister of State Antiquities, Dr. Mohamed Ibrahim, to the Secretary General, Dr. Mostafa Amin, and to Dr. Mohamed Ismail, Director of Permanent Committee and Foreign Missions Affairs. In Luxor, as it has been the case for every year in the past, the authorities responsible of the Supreme Council of Antiquities have been most helpful, in particular Mansour Boraek, General Director of Antiquities in Upper Egypt, Mohamed Asm, General Director in the area of Luxor, and Dr. Mohamed Abd el-Aziz, Director of the Antiquities Department in the West Bank.

The field season has been sponsored by Union Fenosa Gas (UFG), a Spanish gas company whose main activity is based in Damietta (http://www.unionfenosagas.com/en), and by the Spanish Ministry of Culture (http://www.mcu.es).

ARCHAEOLOGICAL WORKS

The rock-cut tomb-chapels of Djehuty and Hery (TT 11–12) are located at the northern end of the Theban necropolis, in the central area of the hill of Dra Abu el-Naga. They were hewn at the foothill, and they are interconnected through a third tomb (–399–). The three date to the early XVIIIth Dynasty, in the first half of the 15th century BC. A Spanish-Egyptian archaeological mission has been working in the area since 2002, conducting consecutive annual campaigns in the months of January and February.

TOMB-CHAPEL OF HERY (TT 12)

The innermost chamber of Hery’s funerary monument measures 5.20 x 6.60m, and it has a central square pillar of 1m each side aprox. As it was the case for Djehuty’s monument, it was filled with debris that fell inside trough two big holes in the ceiling. In this case, one is in the middle, breaking part of the pillar, and the other connects with the inner part of the nearby monument of Baki, located one meter to the east/north and 2.5m higher up the hill.

Once the two wholes were blocked and the debris stopped falling, last season we were able to start excavating around the pillar. The debris contained a number of objects from later funerary equipments, attesting for the reuse of the monument through a long period of time. Since no modern objects were found, it seems that the debris were not removed in the 19th and 20th centuries.

The funerary shaft that once sheltered the burial of Hery was discovered last season, at the south/west side of the chamber. Its mouth is slightly larger than average, 2.40 x 1.10m. The shaft was excavated this season, and ended up being 7.50m deep. The first two meters where mostly thin white powder resulting from burning bones. Not by coincidence, the surface of the shaft’s walls were very smooth, heavily eroded, only for the first two meters down. The material culture is mostly roman: an oil-lamp with burnt bones attached to it, pottery plates and an ibis mummy. Going deeper down, we started pulling up big stones, and the walls were no longer eroded. The material is of a mixed type, ranging from a XXIst Dynasty painted coffin lid, a ramesside inscribed relief fragment, and a neck of a Chipriot jar and other fragments of XVIIIth Dynasty painted pottery.

At the bottom, two opposing burial chambers open, at the west/north side and at the east/south side. The former is still partially blocked with mud bricks. The chamber is quite broad, with the walls and ceiling blackened by fire. It was found filled with animal mummies in wrapped linen packages, untouched since the second century BC. The other chamber, on the contrary, is empty, with the floor completely covered with bird bones. The walls are blackened. The back wall of the chamber has a hole, connecting with a second chamber that seems to reach the burial shaft that opens at the inner room of the tomb –399¬–. The burial chambers and their contents will be investigated next season.

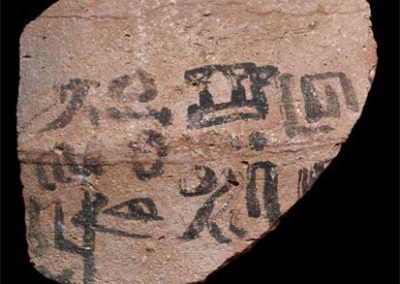

The inner chamber of Hery’s tomb-chapel was fully excavated this season, and a number of interesting objects were found very close to the floor level, among them 5 limestone fragments with relief decoration coming from Hery’s corridor. A bronze figurine of Osiris (14 x 3.8 x 1.3cm) of very good quality, probably Roman period, was found near the west-northern corner of the chamber, within a layer of very thin white powder, resulting from burning human bones. At the other side of the chamber was found a painted wooden board (16.5 x 15 x 1.5cm) with a kneeling figure of a goddess, with the text: «Words spoken by Nephthys, god’s sister, Ra’s eye, mistress of the house of life, may she grant…» Within the debris falling from the tomb-chapel of Baki, we found a pottery ostracon (6.6 x 6.3 x 0.6cm) written in black ink and cursive hieroglyphs containing a passage in vertical columns from the standard text accompanying the fishing and fowling scene.

At the north/east side of the pillar, we discovered the small and almost squared mouth (1.35 x 0.93m) of a second and later funerary shaft, only 3m deep, and irregularly cut. It has one burial chamber, containing a wide range of objects that were at some point thrown inside: (a) a large fragment of relief coming from the inner end of the right wall of Hery’s corridor, showing the back of his mother sitting on a chair; (b) a ramesside sandstone dintel showing the owner adoring Osiris and the goddess of the West; (c) the head of a wooden coffin, with the face painted in red and the wig in blue/green and yellow; (d) the head of a wooden coffin, with a black background and decoration traced in yellow; (e) papyrus fragments that joined together show a sitting figure of the god Osiris; (f) three human skulls and scattered human bones; (g) six animal mummies, probably ibis and falcon, four of them in good condition; (h) one cartonnage falcon mummy mask; (i) a group of 376 complete shabtis (15 of them rais; plus 25 incomplete), backed and painted blue, of the Third Intermediate Period; (j) a group of 268 complete shabtis (one complete rais), backed and painted yellow, of the Third Intermediate Period.

The base of a mud brick wall was unearthed, crossing the entrance to the inner chamber and deviating the visitor to a mud brick staircase leading up to the tomb-chapel of Baki, and/or inside a gallery that penetrates the rock under it. When the mud brick wall was standing in its full height, it protected the area of the rock-wall on which it laid, and it is here where we find the only original wall surface of the inner chamber, still preserving traces of the relief decoration that once had. This circumstance seems to imply that the burning of bones played a role in the erosion and abrasion of the surface of the chamber’s walls that washed out the relief decoration that once covered them.

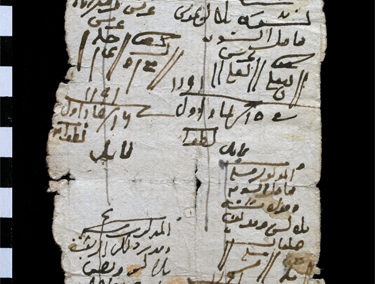

The tomb of Baki was hewn 2.5m higher than Hery, but separated from it only by a rock-wall a meter thick. The tombs of Hery and Baki were interconnected in later times by a well cut passage, and a mud brick staircase was built to safe the difference in height. In one of the walls of the connecting passage, an entrance to a gallery was opened. Near the entrance, three large demotic graffiti were written in red ink. One of them mentions «the burying place» and a scribe named Payef-tjawemawy-Khonsu son of Nes-Min, «the great one of Thot». According to Richard Jasnow, they probably date around 200 BC. Inside the gallery going under the tomb-chapel of Baki, several human bodies have been moved around and mistreated. One was thrown outside, and five others, lying almost stripped, describe a circle. The head and torso of one of them has been carefully placed on top of a mud brick bed at the threshold as if to impress the visitors, and a second one has a funerary cone nailed in his neck. The gallery will be fully excavated in the future.

At the entrance to the gallery, objects of different periods were found mixed up, including several fragments from Hery’s corridor walls, an XVIIIth Dynasty canopic lid in the shape of a human head identified as the goddess Selqet, with a wig painted in black and yellow bands; two cartonnage masks for falcon mummies; a blue fayence djed-pillar; and a group of 167 complete shabtis (10 of them rais; plus 10 incomplete) painted in blue, of exactly the same type as the group found in the second small shaft at the inner chamber of Hery’s tomb-chapel.

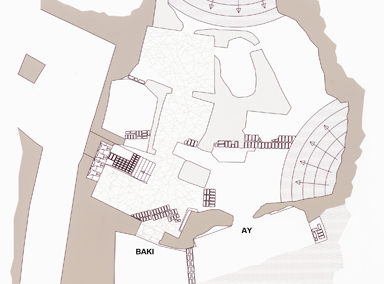

TOMB-CHAPEL OF BAKI

The open courtyard of Baki’s tomb-chapel was excavated in 2005. It was then when we discovered the doorjambs with the owner’s name and tiles, «the overseer of the cattle of Amun, Baki», who must have lived in the mid XVIIIth Dynasty. The inner part of the monument was, however, painted over a thick layer of mortar, and most of the decoration is now gone. The walls and ceiling were reworked to such an extent that the tomb-chapel’s layout is hardly recognizable. In fact, when in 1829 Jean François Champollion went inside to gain access from here into Hery’s corridor, he described it as a «caverne«.

The inner part of Baki’s monument had a 1m layer of sand and stones over the original floor. It was heavily reused in Ptolemaic-Roman period (oil lamps and pottery), and even more so in modern times, in the 19th and mid 20th centuries, when animals where kept inside and a mud brick fireplace was built. The excavation brought to light this season a very carefully designed masonry entrance step, and also part of a biographical inscription that had been later on covered with mud bricks and mortar. The inscription was carved in incised relief and the signs painted in yellow. The text refers to Baki’s duties and proper conduct as overseer of the cattle.

TOMB-CHAPEL OF AY

What seemed to be a huge tomb that was later on enlarged and turned into a cave, ended up being two tombs whose separating rock-wall was at some point completely destroyed. Thus, the excavation brought to light the entrance of a previously unknown mid XVIIIth Dynasty tomb-chapel. The owner could be identified through the large number of funerary cones with his seal impression that were unearthed near the façade: 66. The seal impression reads: «Ay, overseer of the weavers». Five bricks with his seal stamped on two of its sides were also found lying on the ground.

Outside the entrance, other material was found, such as inscribed limestone and sandstone fragments, or eight linen bags containing natron. At the inner side of the entrance, eleven stamped bricks of «the scribe Nebamun» were found. But the most interesting find of all was a complete and well preserved large size mud brick (48 x 24 x 12cm) bearing the impression of an ibis on top of a stand, i.e. the name Djehut(y).

The excavations at both sides of the funerary monuments of Djehuty and Hery are bringing back to light part of the ancient necropolis, showing how the tomb-chapels were arranged one next to the other, in a row, as if they were following a street along the foothill. They are separated from one another only by a rock-wall half a meter thick, and for that reason they were easily interconnected in later times. The density of tomb-chapels here is higher than in other areas of the necropolis due to its symbolic location.

AREA ABOVE THE TOMB-CHAPELS

We have continued clearing the area higher up the hill, with the aim of removing the weight above the tomb-chapels, and eventually unearth the entrance of the tomb-chapels located higher up the hill, in the second and third levels. The material found here is very much mixed up. It is worth mentioning a fragment of a plate (11.4 x 11.6 x 0.8cm) that was used to write a funerary formulaic prayer: «A boon that the king grants, and Amun-Ra-Horakhty and Atum [lord…] in the horizon of (?). Their ropes […] illuminate his two eyes. May he grant (me) to be a spirit in heaven, powerful on [earth…] as he appears in glory in the Western horizon of heaven […]».

SECTOR 10, SPUTH-WEST OF DJEHUTY’S OPEN COURTYARD

At the left side of Djehuty’s open courtyard, a new area of excavation was opened last season. The excavation continued this year and, in a quite superficial level, a large quantity of relief fragments was found, about thirty, some of which belong to the inner walls of the funerary monument of Djehuty (TT 11). Among the material found, it is worth mentioning the feet of a large size limestone shabti of a «scribe Ay», and fragments of a polychrome limestone statue(s). A Saite mummification deposit was also found, integrated by a large tubular vase and fourteen linen bags containing natron. A relevant finding that needs further investigation is a fragment of linen cloth with a text written in black ink, cursive hieroglyphs, and displayed in columns separated by vertical lines. Its condition is not very good, but still Barbara Lüscher has been able to identify chapter 124 of the Book of the Dead.

A very large pottery deposit mostly of the early XVIIIth Dynasty was also found. At the end of the season we collected more than 2,000 vases of various types. Some had plant remains inside. There was very little material other than pots. The group does not seem to be related to a particular burial, but it rather seems to be associated with a cultic practice, maybe the remains of offerings deposited in a shrine. Future excavations in the area may reveal its nature and reason behind it.

The lower chapel rests 1m above the level of the floor of Djehuty’s courtyard, and it has a maximum height of 0.90m. The mud bricks used measure 28 x 15cm. Excavating inside the chapel we found a group of six early XVIIIth Dynasty stick shabtis, two wooden model coffins, and one model sarcophagus of mud (box) and pottery (lid). Three of the figurines are inscribed over a thin coat of whitewash. Two of them bear only a personal name written in hieratic, most probably to be read Ahmose-sa-pa-ir. A third one (14.3 x 2.5 x 2cm), of much better quality, has a longer inscription in six horizontal lines, written in cursive hieroglyphs. It has the standard shabti-formula of this period, and the owner is called Ahmose.

Two of the shabtis were found wrapped in a small linen bandages. Aside of these, other linen cloth fragments were found. Three of them are inscribed. One bears the name Ahmose, and a second piece (20.5 x 10cm) has a label in two vertical columns: «Linen cloth for Ahmose-sa-pa-ir». The third linen has a longer horizontal text in hieratic, unfortunately quite faded away, and its reading is still in its way.

RESTORATION WORKS

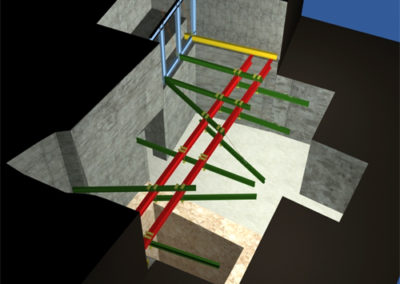

The strengthening of the ceiling of Djehuty’s inner chamber or shrine was one of the main goals of this season. We used for it iron beams to install a new iron ceiling that will secure the original one and protect the visitors below. The structure avoids the installation of supports in the middle of the chamber, what would have interfered with the view of the decorated walls. At the same time, we continued the cleaning and consolidation of the walls of the shrine and central corridor. Mud was carefully removed from the surface, turning visible parts of inscriptions that were hidden underneath. Now the inscriptions and the polichromy of the reliefs can be better appreciated, and also new demotic graffiti that were written on the walls on the second century BC can now be read. Fragments that had fallen from the walls and were recovered in the excavation of the open courtyards are now in the process of being re-attached to their original location, thanks to the collaboration between epigraphers and restorers. This is also the case for the second biographical inscription of Djehuty that was carved on the transverse hall.

The restoration of the XIth Dynasty wooden coffin of Iqer was completed. We prepared and wrapped the coffin, together with the sticks, bows, arrows and pottery that we found associated with his burial, to be transported to the Luxor Museum. The seven gold earrings and the wallet spacers of a girdle (made of cornaline, turquoise and gold) found inside Djehuty’s burial chamber, dating to the early XVIIIth Dynasty, were also made ready to be transported to Luxor Museum. Finally, eleven flower bouquets and one complete jar of the XXIst Dynasty were also moved to the Museum. The transportation of the objects from the SCA magazine near Carter House to the Luxor Museum successfully took place on May 27th 2012, under the supervision of the Director of the Museum Sanaa Ali, assisted by her team of curators.